Slide 1.

Stephen Silberstein, MD: Hello. My name is Dr. Stephen Silberstein. I’m professor of neurology at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, and Director of the Jefferson Headache Center at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. I would like to welcome you today to this Medscape CME Spotlight Panel entitled, “Diagnostic and Therapeutic Challenges of Acute Migraine.”

Slide 2.

What are our learning objectives today? We’d like to evaluate and understand the progression of migraine attacks. We’d like to examine the different stages of migraine attack progression. We would like to discuss and evaluate the different treatment options available for migraine attacks associated with cutaneous allodynia of the head. I am joined today by my colleagues, Dr. Joel R. Saper, founder and director of the Michigan Head-Pain and Neurologic Institute in Ann Arbor, and clinical professor of neurology at Michigan State University in East Lansing, Michigan. And Dr. Fred G. Freitag, who is clinical associate professor at the Department of Family Medicine in Chicago Medical School at Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science in North Chicago, Illinois, and co-director of the Diamond Headache Clinic in Chicago.

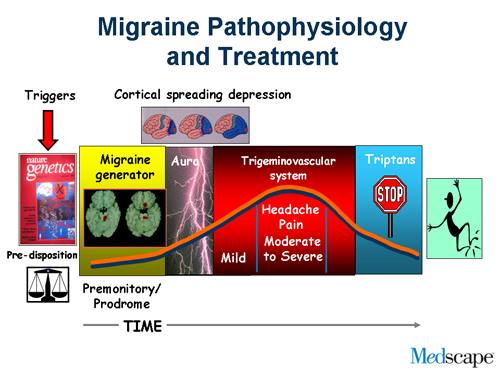

Slide 3.

We begin with an overview of the progression of migraine attack. Migraine is just not a headache or an aura or prodrome. During a migraine attack, it begins with premonitory features. One may have an aura, there’s a headache and the postdrome. Migraine is more than just a headache.

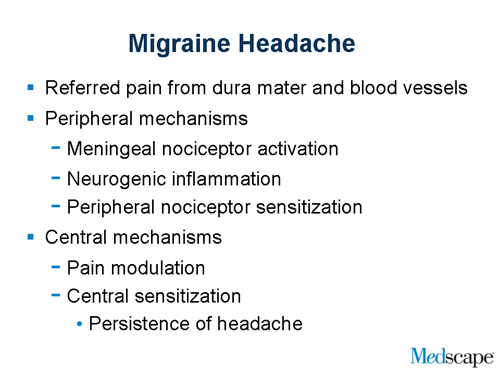

Slide 4.

Where does the headache from migraine begin? We believe it’s referred pain from the dura mater and blood vessels. What do I mean by that? If you have a myocardial infarction, then you get pain in your arm. We believe that migraine pain begins from the lining of the brain and the pain is referred to the head and neck. What happens? The nerve endings become activated. They become inflamed and they become sensitized. I’ll talk about that in a minute. What happens in the brain? There’s pain modulation. Nerve terminals change in the brain itself and this accounts for the persistence of headache.

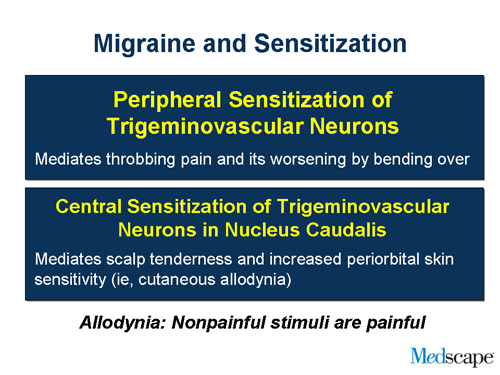

Slide 5.

Peripheral sensitization, what do I mean by that? If you touch your hand, it doesn’t hurt. If you get sunburn and you touch your hand, then it’s painful. The nerve terminals become sensitized. When that happens in the lining of the brain, nerve terminals change and that’s why migraine pain is throbbing and aggravated by movement. When the nerves in the middle of the brain get sensitized, they now respond to stimuli from other parts of the body. That’s called central sensitization and that’s why patients with migraine complain of something called allodynia.

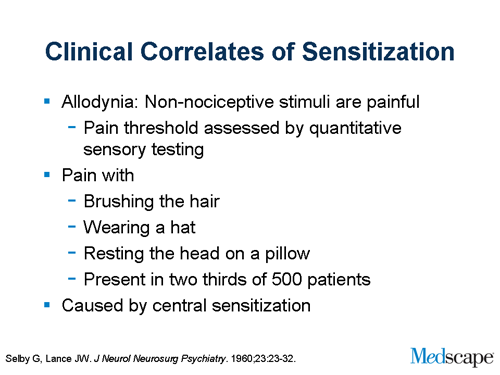

Slide 6.

What is allodynia? Nonpainful stimuli are perceived as painful. What do patients tell us? They can’t brush their hair. They can’t wear a hat. They can’t rest their head on a pillow. And about two-thirds of patients with migraine will have this and it accounts for many of the symptoms of migraine that people complain about that seem bizarre, such as complaints that their hair burns. And this is due to central sensitization.

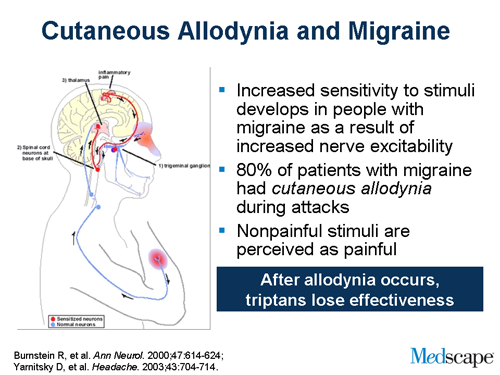

Slide 7.

Why does this matter? As I mentioned earlier, migraine patients develop increased sensitivity to stimuli as a result of increased nerve activity. This occurs in about 75% to 80% of migraineurs. And when they develop subcutaneous allodynia, nonpainful stimuli are now perceived as painful. And why does this matter? After allodynia develops, triptans will lose their effectiveness.

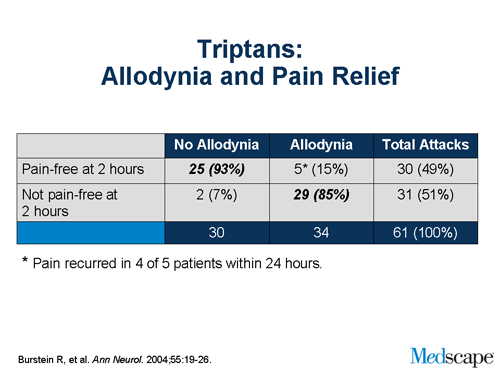

Slide 8.

Rami Burstein did a study a number of years ago. He looked at patients getting a triptan and looked at whether or not they were pain free at 2 hours. In the absence of allodynia, over 90% of the patients were pain free. In the presence of allodynia, only a minority, less than 10%, were pain free at 2 hours, suggesting that allodynia is a marker for failure. And since allodynia takes time to develop, it’s a basis biologically of treating early.

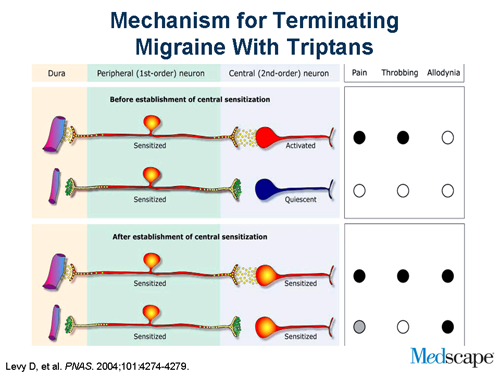

Slide 9.

Now, how do triptans work? The way to look at it is that the trigeminal nerve gets activated. As a result of activation it sends information to the brain stem and the trigeminal nucleus caudalis. If you give a triptan, it blocks communication. If the central nervous system is not activated and sensitized, it turns the process off. Once the process gets going, it’s independent of input from the trigeminal nerve. That’s with allodynia, and patients have these funny symptoms. You give a triptan, you block communication, but the central nerves are still active and that accounts for the fact that the pain doesn’t go away.

Slide 10.

So what does this mean? Treat early. The advantages include decreasing the total duration of suffering, increasing pain-free rates, and reducing recurrence and re-dosing. Delay can lead to allodynia, central sensitization, and treatment failure.

Slide 11.

We would next like to move on to some of the treatment options for migraine attacks associated with cutaneous allodynia of the head. Dr. Saper.

Joel Saper, MD: Thank you, Steve. The principle of treating an acute headache of course begins by making the correct diagnosis. We also have to think about the frequency of the attacks, the intensity of the attack, and the treatability of that individual with comorbid illness. For example we wouldn’t want to give a drug that constricts blood vessels in a patient who has serious cardiac disease or severe hypertension. Confounding factors include medication-overuse headache, which would make the choice of medications a bit more complex, and whether or not there are other factors in that person’s health or emotional background that might govern the way we would approach that particular person.

Slide 12.

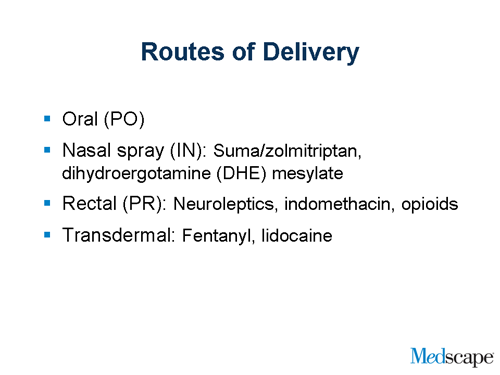

We also have to think about what the most desirable route of delivery would be. There is a gastroparesis, a delay of absorption, in many patients with headache, and Steve, as you have said, getting that blood level up to a therapeutic value early in the course of the evolving attack is very important to gain efficacy. So sometimes we can use oral medicine. We also have nasal spray medicine available. We have rectal routes for some patients, and transdermal routes.

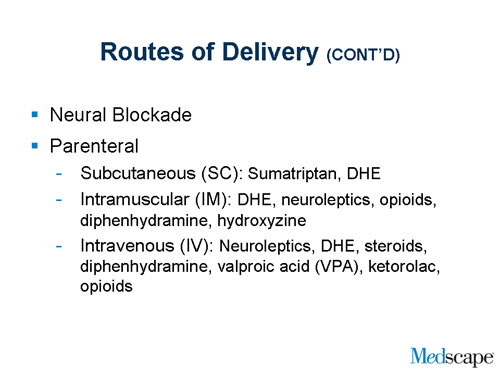

Slide 13.

We have parenteral routes where we give medicine either subcutaneously, intramuscularly, or intravenously. And we have a variety of medicines that can be used in that domain to choose from with specificity for the patient in front of us.

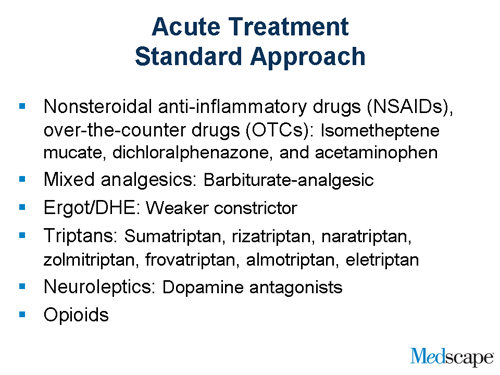

Slide 14.

Now, in the panorama of drugs that we have available to us we have of course over-the-counter medicines and the NSAIDs [nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs]. We have isometheptene combinations. We have mixed analgesics that have a variety of over-the-counter medications in conjunction with barbiturates. We have the ergot derivatives, such as dihydroergotamine, and we have 7 triptans that come in a variety of different formulations including oral and nasal spray and intramuscular injections. We also have other drugs that can be used in the treatment of an acute headache, and we’ll talk about those in just a minute.

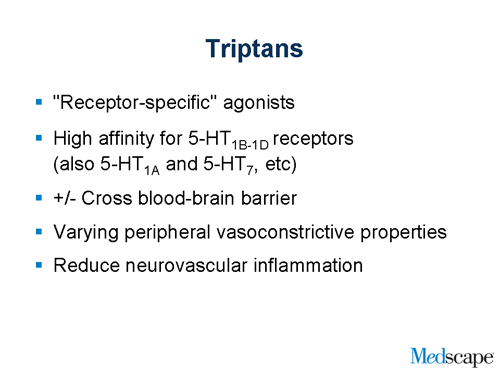

Slide 15.

But if we go back to the triptans for a moment, the triptans are very narrowly focused, specific drugs that work on a few receptors such as serotonin 5HT-1B and D and maybe a few others. But it’s a very receptor-specific drug that has proven to be very effective in the treatment of acute or severe migraine. The structure of sumatriptan, which is the original triptan, is very similar to the structure of serotonin, so in some ways the body perceives triptan as its own transmitter serotonin.

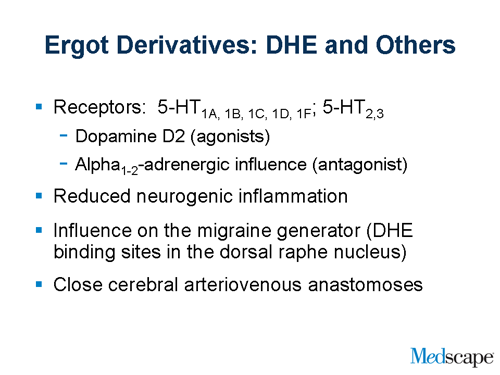

Slide 16.

It’s probably also important to mention as we go through the choice of medicines, that, while the triptans are very narrow in their specificity for receptors, the ergot derivatives can influence a much broader receptor field. There are some patients who do not benefit from triptans, but will benefit from ergot derivatives. So it’s important as we prescribe drugs to keep in mind that simply a failure of one category of medication doesn’t necessarily imply that the person will not respond to another category. In this case, the ergots not only affect the same receptors that the triptans affect, but they [also] go to dopamine receptors and alpha-adrenergic receptors, and so affect a wider field. And for some patients, that’s a better choice of medicines.

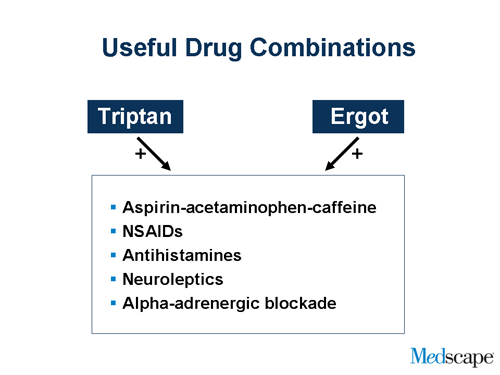

Slide 17.

There are of course useful combinations. We can sometimes combine a triptan with an over-the-counter analgesic or an NSAID. The same can be said about DHE [dihydroergotamine] and the ergot derivatives. We can combine these drugs with antihistamines. We can combine these drugs, the triptans and the ergots, with neuroleptics and alpha-adrenergic blockers.

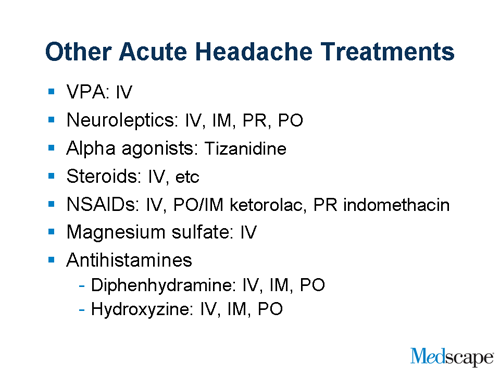

Slide 18.

I should also say that, in the more extreme case, where a patient doesn’t respond to the standard treatment, we do have the ability to give intravenous medicines and there’s a wide variety of drugs that can be used from intravenous valproic acid to intravenous DHE to intravenous chlorpromazine and other neuroleptics, as well as a panorama of other drugs that we sometimes can choose from. And in some difficult cases, we have to do all of the above to terminate that attack.

Dr. Silberstein: So Joel, your basic concept would be take advantage of treating early by either giving the medication early or, if you’re waiting time, try to give a parenteral medication to enhance the rate of the drug which is in the body.

Dr. Saper: That’s right. I think the most important decision that the physician has to make is in his or her particular patient, with a particular health profile and particular timeframe with respect to when the attack began, is to determine what is the best first choice of medication for that patient?

Frederick Freitag, MD: The other alternative is to approach the treatment from the multi-mechanistic point of view; the hydroergotamine with its activity across a range of receptors tends to lend itself to being successful in those patients who already have potentially developed allodynia.

Dr. Silberstein: We actually did a study that showed that.

Dr. Freitag: Right.

Dr. Silberstein: And I think you did, too.

Dr. Freitag: Yes, there are some options I think that we have that we can lay out for clinicians and our patients.

Dr. Saper: I think I can speak for all of us, the advice that we would give to our colleagues that treat headaches is they really have to understand how these different drugs work. They have to understand not only the safety profiles but also the mechanisms by which these drugs work, because some of the drugs are constrictors and some are not, and some drugs affect one part of the brain system and not another. I think that by having a better understanding of these drugs, it is easier to put together a combination of treatments, if that person needs it, in terms of the temporal recognition of where that headache is in its evolution.

Dr. Freitag: Sure, because when the drug fails, you need to look at what can you do as a fall-back option that still is going to have specificity. So being able to use things like neuroleptics in the dopaminergic sites, you can give benefit for some of our patients who have failed the triptans and may be a candidate for something else.

Slide 19.

Dr. Silberstein: Thanks, Fred. I think we’re going to move on. You’re going to give us some case studies to actually help us with some of these points in a practical manner.

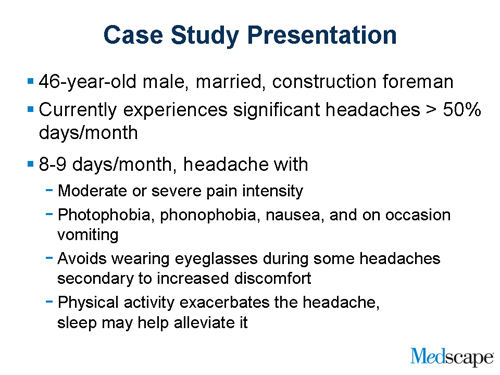

Dr. Freitag: Well, hopefully. Our patient is a 46-year-old male, a married construction foreman. He currently is experiencing significant headaches on roughly half the days of each month. On 8 or 9 of those days, he experiences a headache that is characterized by having pain that is moderate or severe in intensity, and is associated with typical migraine symptoms such as photophobia, phonophobia, nausea, and, on rare occasions, vomiting. Additionally, he finds that wearing eyeglasses when he’s having these headache attacks tends to make things worse; it tends to increase the level of pain he’s experiencing. He finds that physical activity exacerbates the headache. A real key characteristic for many migraine sufferers is to be able to recognize their headaches as well as finding that sleep does have the beneficial effects on alleviating it.

Slide 20.

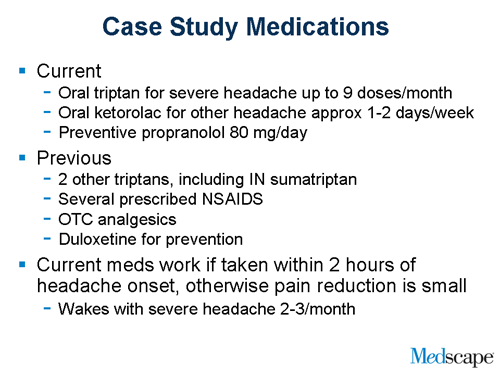

His current medications include an oral triptan. He’s using about 9 doses a month; he’s right at his insurance limit on it. He’s also using ketolorac orally on 1 to 2 days of the week, and he’s been placed on a preventative medication of propranolol at 80 mg per day. He’s tried some other things as well for his headaches. He’s tried 2 other oral triptans and a nasal spray triptan, sumatriptan, with marginal results. He’s tried a couple prescription-level nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories, and he’s taken the whole raft of over-the-counter analgesics that are available. He also tried one of the preventative medications, a neural class antidepressant, duloxetine, as an attempt to control his headaches. He finds that if he takes his oral triptan within the first 2 hours of his headache, in general he can get a good response to it. If he waits too long, holds back on treating, which he’s tending to do because he doesn’t want to run out of his medication, then the ability to stop the headache completely is really diminished. And this is really problematic, because 2 or 3 times a month he’s having the headache already present upon awakening, which puts him behind the treatment curve for successful outcome.

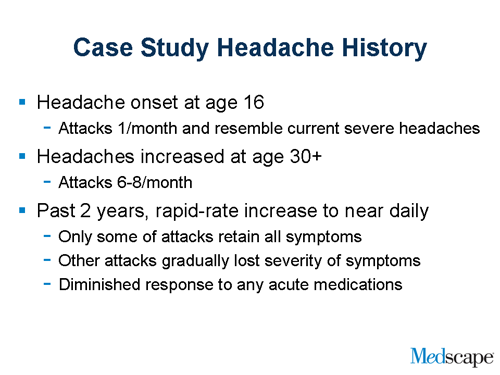

Slide 21.

Past history: his headaches go back to age 16. Back then he was only getting 1 attack a month, and those headaches resembled exactly what he’s experiencing now, and the characteristics are associated with the most severe headaches he’s experiencing. As he got a little bit older and moved into more responsibility with family and work, his headache frequency increased to 6 to 8 per month. In the last 2 years, he’s had a very rapid increase in his headache frequency to the point where he has a near daily headache pattern. Only a part of these headaches still retain all those original migraine-like symptoms, whereas others have gradually had a diminution in the severity of the associated symptoms to the point where they almost resemble a tension-type headache. He’s also found that his response to acute medications has diminished significantly over the course of time.

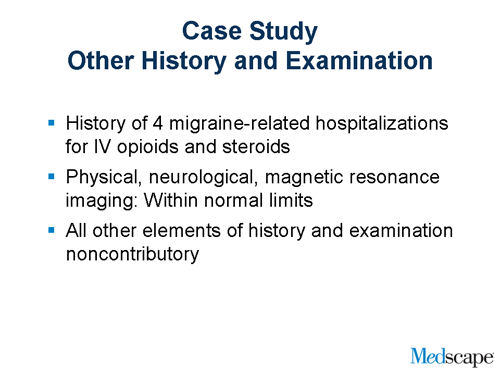

Slide 22.

Other history that may be of importance: he’s had 4 migraine-related hospitalizations, which were treated with IV [intravenous] opioids and steroids. They were helpful to get him out of the attacks, but not very specific, as we know. His examination — physically, neurologically, and by diagnostic scanning — has all been normal. The remainder of his history is really unremarkable and noncontributory to his situation.

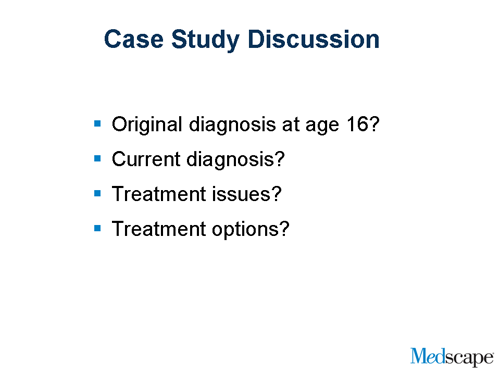

Slide 23.

So we have a complex case here. What would you say would be his original diagnosis at age 16?

Dr. Silberstein: Well, I think that you clearly pointed out he had episodic migraine at age 16.

Dr. Freitag: And now?

Dr. Saper: And now he has chronic migraine.

Dr. Freitag: Yes, right.

Dr. Saper: What I don’t know from your presentation is the frequency of use of his abortive medicine. In other words, was some of the progression to the chronic migraine circumstance prompted in part by the overuse of his abortive medication?

Dr. Freitag: Well, he certainly was pushing the limits on his triptans all the way along and certainly using a great deal of over-the-counter analgesics as part of his treatment.

Dr. Silberstein: So what’s the chicken and what’s the egg? Do you have more headaches because they take more medicines or do you take more medicines because you have more headaches? That’s the question, isn’t it?

Dr. Freitag: That is always the challenge. That’s really, that’s one of the calls that we have to make for our patients that have these challenging situations. We try to be specific in our acute therapy and in early intervention with preventive approaches, whether through lifestyle or prescriptive medications, to help ramp down the tendency to have so many headaches so that our patients are not tempted to overuse their medications.

Dr. Saper: Yes, but from a practical point of view, at the point that many of us see these patients, it almost doesn’t matter which came first because we have both a headache process and a medication overuse process to address. And so our problem now is, how do we take this person back from a frequency of use? I think we all would agree on average that it would be more than 2 to 3 days of use of these abortive medicines. How do we take that person back from that level and at the same time address the primary process which was there since he was a teenager?

Slide 24.

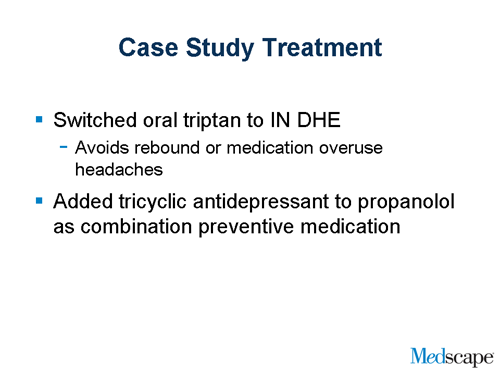

Dr. Silberstein: So what did you do, Fred?

Dr. Freitag: What do we do? Well, one of the things we did was we shifted him from an oral triptan to an intranasal dihydroergotamine preparation. I like that in this kind of situation, because it really frees us up from the significant worry of medication overuse, rebound effect from the acute migraine therapy, and opens up some treatment options for him. One of the things that we will commonly do in a patient like this is to put him through a course of dihydroergotamine, either in hospital if they have other issues or even on an outpatient basis over the course of several days, to try to help break up that pattern of headaches and move him away from that daily headache regimen. Beyond that, I also changed his preventive medication strategy. I went to more of a combination tiered approach. Since he had a partial response to propranolol, I added a tricyclic to his regimen, kind of a rational pharmaceutical approach like one would use for high blood pressure or diabetes.

Dr. Silberstein: Like we wrote about in our chapter?

Dr. Freitag: Yes. Exactly.

Dr. Saper: It’s very interesting. This patient seems to have had the right treatment along the line, but didn’t really find it possible to avoid that progression of headache. It didn’t seem from your presentation that there were too many comorbid problems in this individual that would prevent him from otherwise responding to treatment, but it seemed as though the course of his illness progressed nonetheless. Let me ask you a question: the propranolol that he was taking, was that a single dose of propranolol or was that a divided dose of the short-acting propranolol?

Dr. Freitag: No, he was using one of the long-acting capsule formulations of it. You know the other thing that’s really missing in this case, which we hadn’t had a chance to explore at the time of his history, was looking at psychological issues, other behavioral issues, and the role of physical medicine in this patient. We really hadn’t examined those issues yet.

Dr. Saper: Right. You know my own experience with the propranolol as a preventive drug is that the long-acting formulations, such as 80 mg, doesn’t really cover the entire day and doesn’t really provide a blood level throughout a period of time to effectively prevent [migraines] in a 24-hour timeframe. And I have a personal preference that when we use propranolol, we use the short-acting form, and we dose it 3 or 4 times a day, which to me provides a much better coverage for prevention.

Dr. Freitag: I would agree with you, though the issue I always find is one of compliance. As we move to the 2- and 3-times-a-day regimens, we increase their likelihood of missing a dose, especially that afternoon dose. But I would agree with you. Ideally a morning, an afternoon, and a heftier bedtime dose of the propranolol can be very effective. I like to stage my preventive medications with a little heavier dose in the evening, especially when they have early morning headache. I try to get relatively good coverage for them pharmacologically.

Dr. Silberstein: I agree with both of you. I do something different with the long-acting preparation. I will use it, but use it twice a day because I agree with Fred that compliance is a major issue, and if you give people 3 times a day, they wind up taking it once or twice. The other issue with propranolol is that the dose is so variable that sometimes you really have to push it.

Dr. Saper: You really do. I think that we learned early on in the 70s, when propranolol became so important, that a long-acting dose was just not enough to cover the day, and giving a twice-a-day, long-acting dose at a higher level than you would otherwise give, was the way to control patients. That’s right.

Dr. Freitag: Do you find much difference, Joel, since you’ve had a lot of experience and written a lot about the ergotamine preparations, in efficacy issues, tolerability issues between the older ergotamine tartrate vs dihydroergotamine, in your migraine sufferers?

Dr. Saper: Well, I think that our colleagues sometimes don’t realize is that ergotamine tartrate — the old drug we had in the 70s and 80s and even long before that — is not what dihydroergotamine is today. It’s an ergot preparation to be sure, but dihydroergotamine is much more of a venous constrictor and not much of an arterial constrictor.

Dr. Freitag: Right.

Dr. Saper: As you implied a minute ago, we don’t really think that one gets into medication overuse headache with dihydroergotamine. I think that’s probably arguable, but I agree with you that the other drugs can lead us into overuse syndromes.

Slide 25.

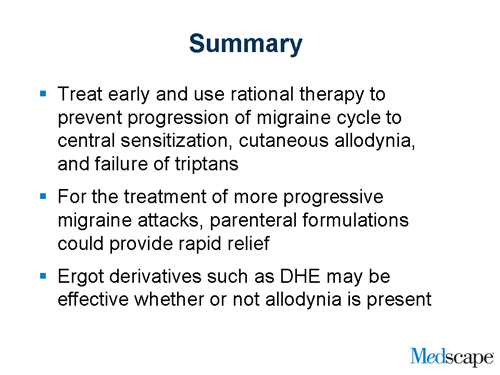

Dr. Silberstein: I want to thank my colleagues, Dr. Saper and Dr. Freitag. I thought that was a very interesting discussion. I think we can summarize the following: treat early if you can because it prevents the development of central sensitization manifest by allodynia and the failure of triptans; intravenous and other parenteral formulations give you faster action and this can overcome the problem; and, as we’ve talked, medications such as dihydroergotamine may be effective whether or not allodynia is present. Thank you.

This activity is supported by an unrestricted educational grant from Valeant Pharmaceuticals.

Authors and Disclosures

As an organization accredited by the ACCME, Medscape, LLC requires everyone who is in a position to control the content of an education activity to disclose all relevant financial relationships with any commercial interest. The ACCME defines “relevant financial relationships” as financial relationships in any amount, occurring within the past 12 months, including financial relationships of a spouse or life partner, that could create a conflict of interest.

Medscape, LLC encourages Authors to identify investigational products or off-label uses of products regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration, at first mention and where appropriate in the content.

Author

Frederick Freitag, DO

Clinical Associate Professor, Department of Family Medicine, Chicago Medical School at Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, North Chicago, Illinois; Diamond Headache Clinic, Chicago, Illinois Disclosure: Frederick Freitag, DO, has disclosed that he has conducted research for Advanced Bionics, AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Ortho-McNeil Neurologics. Dr. Freitag has also disclosed that he has served as a consultant to Allergan, AstraZeneca, Capnia, Endo, Merck, NuPathe, Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceuticals, Valeant Pharmaceuticals, and Zogenix, Inc. Dr. Freitag has also disclosed that he has served on the speaker’s bureau of GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceuticals, and Valeant Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Freitag has also disclosed that he is a member of the Board of Directors for the National Headache Foundation and the Diamond Headache Clinic Research and Educational Foundation.

Joel Saper, MD

Clinical Professor of Medicine (Neurology), Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan Disclosure: Joel Saper, MD, has disclosed that he has received grants for clinical research from Merck, Obagi Medical Products, Pfizer, Endo, GlaxoSmithKline, Neuralieve, ProEthic, Johnson and Johnson, Alexia, Allergan, Cypress, Eli Lilly, Advanced Neuromodulation Systems, Inc., MAP Pharmaceuticals, Medtronic, Torrey Pines, and Schwarz. Dr. Saper has also disclosed that he has received grants for educational activities from Merck, Obagi Medical Products, and Purdue Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Saper has also disclosed that he has served as an advisor or consultant to Obagi Medical Products, Neuralieve, Allergan, Advanced Neuromodulation Systems, Inc., and Medtronic.

Stephen D. Silberstein, MD, FACP

Professor of Neurology, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Director, Jefferson Headache Center, Thomas Jefferson University Hospital. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Disclosure: Stephen D. Silberstein, MD, has disclosed that he is on the advisory panel, speaker’s bureau, or serves as a consultant to AGA, Allergan, Capnia, Inc., Endo Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, MAP Pharmaceuticals, Medtronic, Merck, NuPathe, Pfizer, Valeant Pharmaceuticals, and Vyteris. Dr. Silberstein has also disclosed that he has received research support from AGA, Advanced NeuroModulation Systems, Allergan, Boston Scientific, Endo Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly, MAP, Medtronic, Merck, NuPathe, and Valeant Pharmaceuticals.

Editor

Anne Roc, PhD

Editorial Director, Medscape Neurology

Disclosure: Anne Roc, PhD, has reported no relevant financial relationships.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.