The largest clinical trial to date of out-of-hospital hypertonic resuscitation shows it does not improve outcomes after traumatic brain injury. The disappointing results call into question the idea of emergency-response fluid intervention.

“While this does not preclude a benefit from such treatment were it administered differently,” the Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium investigators report, “at present there appears to be no compelling reason to adopt a practice of hypertonic fluid resuscitation for traumatic brain injury in the out-of-hospital setting.”

The results are published in the October 6 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association.

“The bottom line,” lead investigator Eileen Bulger, MD, from Harborview Medical Center in Seattle, Washington, told Medscape Medical News, “is that administering a single bolus of 7.5% saline with or without dextran in the prehospital setting does not improve long-term outcome following traumatic brain injury.”

|

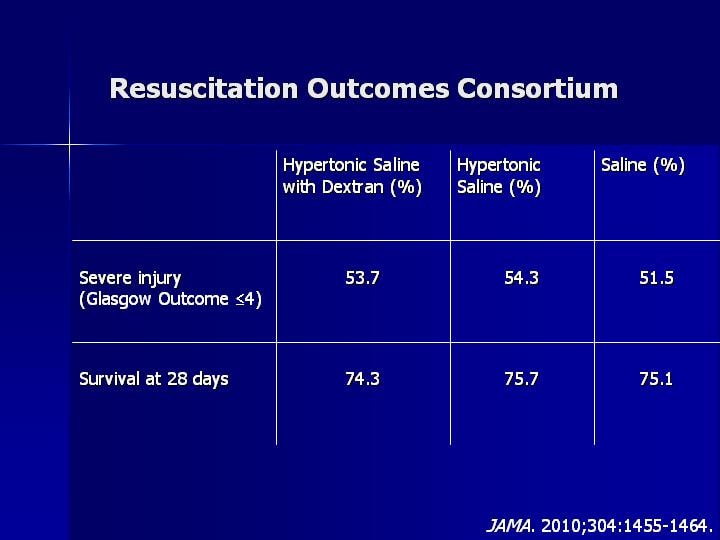

| Investigators saw little difference between treatment groups. |

During an interview, Steven Giannotta, MD, from the University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine, Los Angeles, said he hopes this won’t deter clinicians from continuing in-hospital interventions. “I’d hate to see people overinterpret these results,” he noted. “In hospital, we have to control intracranial pressure so it should be business as usual.”

Dr. Bulger said she is less certain. No studies, she pointed out, have demonstrated an improvement in clinical outcome.

Still, there has been some evidence of benefit. Previous studies, using saline concentrations ranging from 1.6% to 23.4%, have documented reductions in intracranial pressure and improved cerebral perfusion.

Hypertonic fluids are said to restore cerebral perfusion, limit edema, and modulate inflammatory response to reduce neuronal injury after traumatic brain injury.

“More studies are needed of this approach in the hospital,” Dr. Bulger said.

Dr. Giannotta agrees that more study is needed, but is adamant about the importance of in-hospital intervention. “Intracranial pressure kills head injury patients,” he said.

Randomized Clinical Trial

This new multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial comprised 114 emergency medical services agencies in the United States and Canada. Patients had blunt trauma and a prehospital Glasgow coma score of 8 or less. The study consisted of 1282 patients without hemorrhagic shock. Six-month outcomes data were available for 85% of patients.

Investigators found no difference in neurologic outcomes between the 3 groups. Patients had about the same proportion of severe traumatic injury. There were also no statistically significant differences in the distribution of Glasgow Outcome category or Disability Rating Score by treatment group. Survival at 28 days was also about the same in all groups (P = .88).

“We hoped that giving this higher concentration early after injury would show a greater impact on outcome, but it did not,” Dr. Bulger said.

Intracranial pressure kills head injury patients.

The primary limitation of the trial is that traumatic brain injury management in the hospital was not controlled. Not all patients with severe injury received intracranial pressure monitoring, and the timing of monitor insertion was inconsistent. On the basis of neurosurgeon preference, some patients received hypertonic fluids after hospital arrival and others were treated with mannitol.

Despite the study’s limitations, Dr. Giannotta said he is encouraged by this large prospective study of traumatic brain injury. “There has been a lot of skepticism about randomized clinical trials in this area, and I’m glad this group was able to pull it off. This is very exciting and proves it can be done.”

Dr. Giannotta questioned whether the Glasgow Outcome Score used in the trial was masking evidence of subtle benefits of treatment. It is a “crude scale,” he said, noting that he is not convinced the hypertronic fluids have no benefit at all.

“I’m glad the researchers sound so optimistic and will continue studying this. I think what we can conclude from this trial is that expensive resources are not necessary as part of the emergency response at the venue of injury, and might best be reserved for the hospital environment.”

New studies will be needed, say investigators, to confirm in-hospital treatment.

The Resuscitation Outcome Consortium is supported by a series of cooperative agreements with 10 regional clinical centers and 1 data coordinating center from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute in partnership with the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Institute of Circulatory and Respiratory Health, Defence Research and Development Canada, and the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. The researchers have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

JAMA. 2010;304:1455-1464. Abstract

Tags: News, Rianimazione

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.